‘I don’t think of it at all as a gift’: Why it’s complicated being a gifted child

They’re sharp, curious and prone to boredom or even bullying at school. Far from the smartypants cliches, some gifted children hide or stop learning. What is giftedness? And what’s life like for kids with stratospheric IQs?

NOVEMBER 3, 2023

Isabella, a slip of a thing with bright, curious eyes, is in many ways like any other 11-year-old. She lives with her mum and dad and big sister in a suburban house filled with games and puzzles, plays sport, goes to the movies with her friends and loves her dog, an adorable barky spaniel-something-cross resembling a mop that’s lost its pole.

In conversation, though, it quickly becomes apparent that Isabella – not her real name, for reasons that will become clear – is a bit different to other kids her age, thanks to an adult-like vocabulary and a tested IQ that puts her into the top 1 per cent of her age group for intelligence. “I am highly gifted,” she says. “But I don’t think of it at all as a gift. Because the struggles of it are quite hard most of the time.”

Indeed, being “gifted” in Australia is a mixed blessing, as Isabella’s parents have learned to their chagrin. Educators don’t always know what to do with a child who is not only “bright” but academically years ahead of their contemporaries. Other parents might dismiss a gifted child as the product of middle-class hot-housing, manufactured to somehow gain an unfair advantage – which is why many of the gun-shy families we interviewed requested anonymity. There’s not even a common understanding of “gifted” in this country. It is often lumped in with “talented” which, while related, can be something entirely different. Even the word itself can be seen as problematic, perhaps implying that some children are more special, lucky or “blessed” than others – anathema in our supposedly egalitarian society.

So, what is giftedness? And what is life like for children such as Isabella?

What is a gifted child?

In popular culture, the gifted child is most often portrayed as a curiosity: bookish, nerdy and capable of impressive stunts such as performing complex calculations in their head or recalling pi to a hundred decimal places. Think Doogie Howser, MD, the youngest doctor in America; Big Bang Theory‘s Sheldon Cooper, who speaks Klingon and received his PhD at 16; Lisa Simpson’s unappreciated science-fair projects; or Roald Dahl’s Matilda, who reads Dickens’ Great Expectations aged four and three months, much to her anti-intellectual parents’ dismay.

Prodigies do pop up in real life. Mozart wrote Trio in G major when he was 5. US philosopher Saul Kripke had taught himself ancient Hebrew by 6. Mathematician Ruth Lawrence, who went to Oxford University at 12, became its youngest graduate at 13. Singaporean wunderkind Ainan Celeste Cawley passed his year 10 chemistry exam when he was 7 and, yes, could recite pi to 521 decimal places by the age of nine. Which is a lot.

The notion of “giftedness” in children, at least as we understand it today, dates back to 1905, when Frenchman Alfred Binet devised the first modern IQ test, to reveal a child’s abilities compared to others of the same age. Controversial US psychologist Lewis Terman (more on him later) built on Binet’s work with a long-term study of children with high IQs and a doctoral dissertation titled Genius and stupidity: A study of some of the intellectual processes of seven “bright” and seven “stupid” boys.

Yet, a century later, what constitutes giftedness is still being debated. Some educators deny its existence entirely or say, with a roll of the eyes, that it is no more than a fantasy of pushy parents. Some take the view that all children have a particular gift of their own. Others conflate giftedness with talent when the two are often discrete: a gifted child may have been born with great potential but not have explored or displayed it. (Canadian psychologist Francoys Gagne is often cited for his theory that distinguishes giftedness from talent, offering explanations on how natural abilities can be developed into specific skills.)

‘It is impossible to paint a single picture of a gifted student … A gifted student may have exceptional abilities in some areas but be average, or even below average, in others.’

Another common definition of giftedness is simply as demographic rank – the top X per cent of children, measured by academic achievement, in a given cohort. In Australia, that’s typically given as 10 per cent, which would apparently mean two or three children in any particular classroom are “gifted”. Singapore, more exacting, originally steered just .25 per cent of its brightest children – those who demonstrated “outstanding intelligence” – into its Gifted Education Program schools, originally modelled on an Israeli system from the 1980s (it has since widened its scope to 1 per cent). Across the US, the definition is commonly that of a child who performs at, or shows the potential to perform at, a remarkably high level compared to their same-age peers, in an intellectual, creative or artistic area.

Yet psychologists are trained, says veteran child psychologist Judy Parker, to confine giftedness to the top 2 per cent of the intelligence bell curve, measured by the currently recognised IQ tests (a slightly controversial and imprecise tool but probably the best we have for now).

“There are no agreed definitions of giftedness and talent,” admitted a Victorian parliamentary inquiry in 2012, which settled on the catch-all description of gifted students as “young people with natural ability or potential in an area of human endeavour”.

Nor is “giftedness” necessarily able to be quantified, the inquiry noted. “It is impossible to paint a single picture of a gifted student … Gifted students are not a homogenous group. They come from all socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds. Their gifts may be across a vast array of different domains, from academic to creative to interpersonal. A gifted student may have exceptional abilities in some areas but be average, or even below average, in others.”

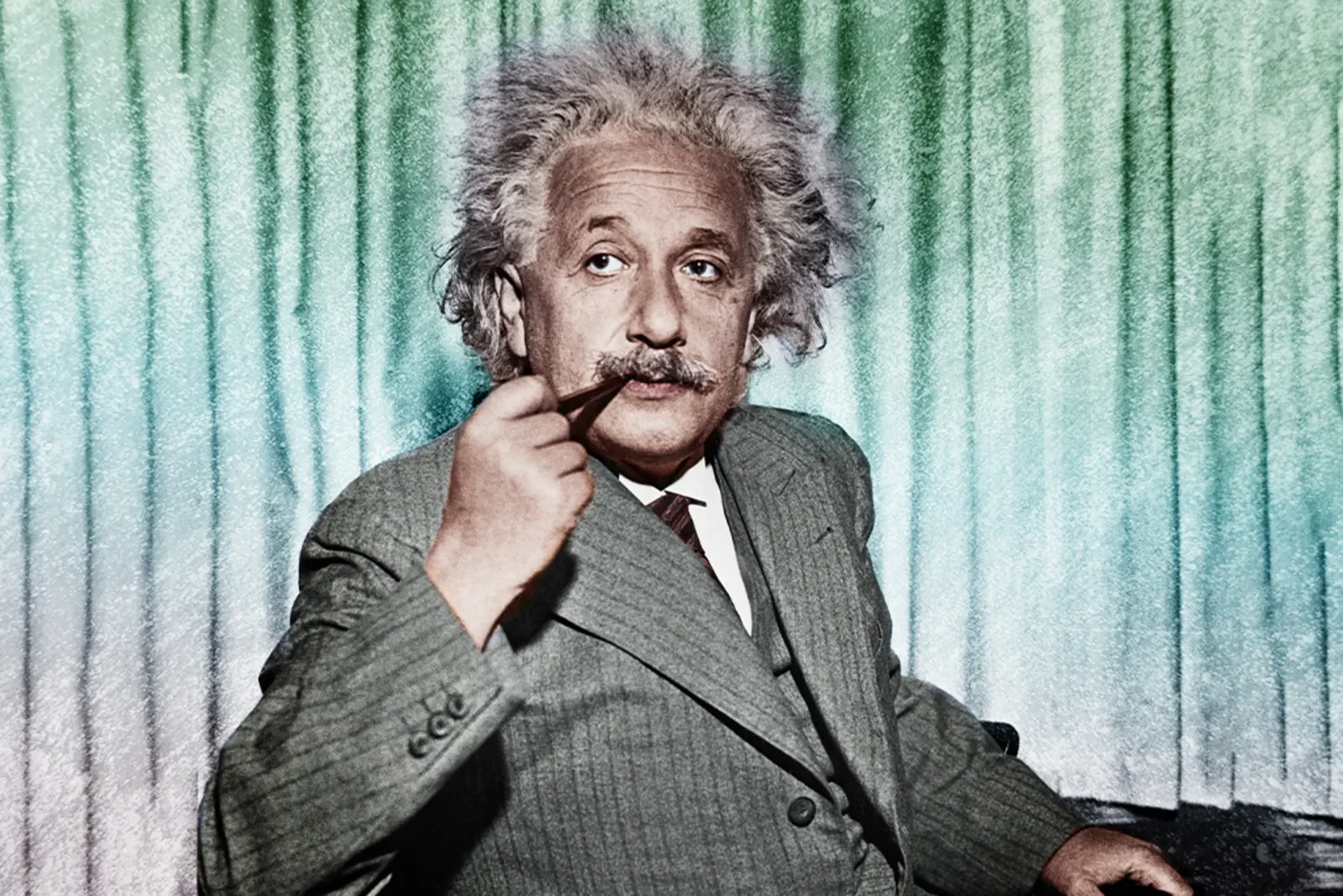

A late bloomer, physicist Albert Einstein did not speak in full sentences until he was 5. GETTY IMAGES, DIGITALLY ALTERED.

How do you recognise a gifted child?

It’s not always easy. As teachers will tell you, the number of parents who declare their child gifted vastly outnumbers the statistical reality. Then, there are the truly gifted children who mask their intelligence to fit in with their peers. Not to mention those who later turn out to have an IQ in the gifted range who initially present with learning behaviours that can suggest autism or ADHD. Many of the parents we spoke with have had their children assessed by psychologists after noticing unusual or odd behaviours, when their child struggled to fit in at school, or when they started to engage in disruptive behaviours in the classroom.

A handful of children – those with an IQ found in only one in 10,000 people or more – likely think differently in ways the rest of us cannot begin to comprehend. They may be top of their class or, as physicist Stephen Hawking was as a child, seem to be away with the fairies.

For argument’s sake, though, being “gifted” in a general sense can be described as possessing an intellect that processes information faster, learns concepts quicker and retains knowledge more readily than most, allowing it to exponentially explore ever more complex ideas and to make increasingly insightful connections. “They learn rapidly, they have an excellent memory and they reason well. These are the sorts of characteristics I’d note,” says Judy Parker, who has spent much of her career testing for giftedness.

For these children, sometimes but not always, maths or language skills might come early and easily; reading might be absorbed, long before tuition, as self-evident; a child hungry for knowledge might temporarily nurture an alarmingly deep interest in an esoteric subject such as black holes or London bus routes; typically, they will have a precocious vocabulary full of spelling-bee words.

The IQ-measuring tools that psychologists use to identify giftedness include the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, which tests for verbal comprehension, visual-spatial abilities, fluid reasoning, working memory and processing speed. IQs (again, somewhat controversially) are plotted on a bell curve, with most of us in the middle, clustered around an average of 100, and exponentially fewer of us at the edges, until there is just one person in all of humanity on the far horizon. An IQ of 160 on this scale is rare, one in 10,000 or more. The ranking ceases to be calculable beyond a point. An IQ score is not an absolute number, though. A child might test differently in different circumstances, such as if they are tired or hungry.

Some of the parents we spoke with are happy to share their child’s IQ as a figure; others prefer to speak in terms of “moderately” or “profoundly” gifted, or where their child sits in a percentile of the population.

Helen, a mother we spoke with, laughs as she remembers her son’s early precocity. He was able to recite the alphabet as a two-year-old, a recognised signifier of exceptional giftedness, according to US educational author Deborah Ruf. Then a family friend told him, jokingly, that he wouldn’t truly “know” his alphabet until he knew it backwards. Says Helen: “And so he just rattled it off backwards without giving it a second thought.” Several years later – her son is now 11 – Helen took him to be assessed after he had issues fitting in at school and he recorded a WISC IQ score heading towards the improbable end of the bell curve’s X axis. He’s currently interested in aeroplanes, both the paper kind and real ones – he likes itemising the subtle differences between a Qantas A380 and one flown by Emirates.

The Barbie movie was funny but none of her friends understood the adult-oriented jokes, ‘which was really awkward’.

Isabella wasn’t doing algebra in her cot but did have proper conversations with her mum at 18 months, which, a child health nurse pointed out, was quite unusual, after asking whether she had started putting two words together. Her family later had her psychologically assessed, thinking she might have an autism disorder. It turned out she actually had an extraordinarily high IQ.

A decade on, she has just aced a test on a book that she’d read only the start of because she had “managed to infer the rest”. The Barbie movie was funny, she says, but none of her friends understood the adult-oriented jokes, “which was really awkward”. And even though she only recently started learning Mandarin she no longer needs to parse the subtitles when they play Chinese films at school because “I can kind of understand it now”, she says, proudly reciting a long phrase.

Yet, a perpetually active brain like hers has its drawbacks. “Birthdays are not easy for Isabella,” says her mum. “By the time we come to the birthday, she’s already calculated how many days she has left to live, how many days the dog has left to live, grandma has left to live. She’s able to reduce the bigger picture into the main facts that aren’t always wonderfully positive.“

Siblings will typically fall in a similar IQ range, though their “gifts” might be quite different. And high intelligence is not always demonstrated at a young age: Hawking was reportedly a late developer, never more than halfway up his class. Albert Einstein (wonderfully played, incidentally, in Oppenheimer by Tom Conti) didn’t speak in full sentences, according to some of his biographers, until he was five. (Perhaps he had better things to think about.) Robert Oppenheimer himself was probably a gifted child: he described himself as “an unctuous, repulsively good little boy”, grade-skipped, read widely and would later teach himself Sanskrit. “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds,” he famously quoted from the Bhagavad Gita after the Trinity atomic test in 1945.

Can you ‘manufacture’ a gifted child?

Some argue that with the right educational techniques, many, if not most, children can achieve at a level of a mildly gifted child. The idea is either that all children are potentially gifted, or that gifted children are the product of coaching and parental effort, not some kind of magic they carry from the womb.

“Research is clear that brains are malleable, new neural pathways can be forged, and IQ isn’t fixed,” says Wendy Berliner, co-author of Great Minds and How to Grow Them from 2017. “Most Nobel laureates were unexceptional in childhood,” she writes.

Much more important, this argument goes, is perseverance, effort and quality teaching – much like the 10,000 hours theory to gain mastery over any particular discipline.

Then there’s the philosophy that all children are gifted in their own way, that every child surely has a special talent that might set them apart. “The great teachers and the great schools find the gifts in every student,” agrees Deborah Harman, an educator of 45 years and one of the leaders in Victoria’s accelerated learning program, noting: “All students – especially those who are gifted – need to feel a sense of belonging to their classes and their peers.”

And yet, there are the children – the alphabet boy, for one – who seem to be different right out of the blocks, behaving in ways no parent could have confected.

Elissa McKay, a mum of a gifted 10-year-old, Finn, grew so frustrated with the myths surrounding giftedness that she compiled her own “primer”, a kind of online booklet widely shared in the internet forums that some parents of gifted children inhabit (largely to share tips, schools advice, war stories and to ask the perennial question: is my child gifted?).

We meet at Elissa’s home on the leafy outskirts of Melbourne, where Finn has just celebrated his birthday, which meant the long-awaited acquisition of a new yo-yo (yes, the craze has come around once again) and the surprise adoption of a kitten.

Like many gifted children, Finn was reading fluently three years before he started school and, when he did start school, he was reading at high-school level, says Elissa. But he had something of a mixed educational journey until he was grade-skipped two years (three years for maths). Before then, says Elissa, “his reports were really mediocre”. It’s a myth that gifted children need no educational support, she says. This is one of the subjects she addresses in her primer, along with the notions that gifted children are best treated just like their peers (she says they’re not) and that they eventually “level out” (she says they never do).

Indeed, Andrew Attard is showing few signs of levelling out. His mother, Julia Lewthwaite, recalls taking him for a check-up at a child and maternal health centre when he was six months old. “He started pulling puzzles from a shelf and actually completing them. The nurse basically said to me, ‘I think your child might be gifted.’” By age three, he was reading, she recalls, “and that’s where the real craziness started”. “He wanted to go walking down all the streets, reading all the street signs, reading all the house names, the house numbers.”

Andrew was tested and found to be in the “profoundly gifted” range, about one in 30,000 students. Now 15, he is about to become the youngest student to complete the NSW HSC.

If you want to “manufacture” a gifted child, you’re probably best off starting with two smart parents. Many of the families we spoke with professed to be surprised when their offspring tested in the gifted range, but it usually turned out they had a rocket scientist for an aunt or an uncle.

“Both my parents, I’m sure, are profoundly gifted,” says another mother of gifted children. “My parents met at Oxford (university), my husband and I met at Oxford, there isn’t anyone without a PhD, you know. It’s just snowballed in our family.” Helen, meanwhile, now suspects her husband, who went to a selective school, is gifted and that she might have been herself had she been identified as such, although her focus as a child brought up by a struggling single mother was survival, not excelling academically. “I had a very different journey in that respect.”

Why is giftedness sometimes considered controversial?

As US cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead once observed: “Neither teachers, the parents of other children, nor the child peers will tolerate a wunderkind.” Every parent we spoke with was extremely wary of being portrayed as pushy, boastful or downright deluded. Some preferred to reveal just first names; others asked to remain anonymous (although Isabella is the only pseudonym we have used).

“People talk,” says Kate, whose daughter Libby, 10, ploughed through all of her prep-level books almost immediately when she started school and had to go up a year. “A mum might come up to me and say, ‘Oh, my daughter said how fantastic Libby is at maths’ but the natural inclination is to downplay it.” All kids just want to fit in, she says. “I think a lot of people make the assumption that kids that are really smart must be egotistical, and they must walk around thinking they’re smarter than everyone else but it’s usually the opposite. They usually try to hide their true self.”

And while some parents, unsurprisingly, can’t help but show a little pride in their children’s precocity, others resolve to treat their offspring as “normal”. One mum whose children have tested with IQs in the 99.9 percentile is more interested in raising them to be good citizens than encouraging what she calls “party tricks”. “They didn’t teach themselves to read or speak Russian or anything like that. They’re just normal kids who pick things up quickly.”

Giftedness can provoke discomfiting notions of a handful of children belonging to an elite group that, by definition, excludes the “non-gifted” masses. Indeed, early IQ tests were developed with more than a dash of eugenics – the debunked pseudo-science that flourished in Victorian and Edwardian eras. One early test had the stated goal of “curtailing the reproduction of feeble-mindedness and the elimination of an enormous amount of crime, pauperism and industrial inefficiency”.

US psychologist Lewis Terman, who revised the work of Binet to produce the first versions of today’s Stanford-Binet test, was a eugenics fan. Yet he was also determined to challenge the contemporary prejudices against gifted children, particularly that they were physically weak and anti-social. In an extraordinary long-term study, he recruited 643 children of various ages and published five volumes of findings over 35 years. While he – weirdly – referred to his subjects as “Termites”, his conclusion was that gifted children, by and large, thrived both in their professional and personal lives.

Concerns about how IQs and educational potential are tested continue to inform the approach to gifted education in the United States. New York City scrapped a standardised test that, according to The New York Times, “foreclosed opportunity for thousands of Black and Latino children” because of its biased cultural references.

“I know IQ tests get a really bad rep,” says Elissa McKay. “But they’re highly accurate at measuring what they measure. They don’t measure potential for success. They don’t measure for potential for happiness. But they do measure a small subset of characteristics associated with intellectual potential.”

Psychologist Judy Parker also believes they are an effective tool. “It’s the best quick and comprehensive and individualised assessment, if done by a psychologist experienced in the field.”

Physicist Stephen Hawking achieved only middling grades as a boy. GETTY IMAGES, DIGITALLY ALTERED

Why do some gifted children underachieve?

If your child is so smart, how come they’re not top of the class? This refrain was familiar to many of the families we spoke with. Many have spent years persuading educators to let their child skip a grade or to be given more advanced work, only to be told their supposedly gifted child isn’t even keeping up with their current grade levels.

These children are not magical: some stuff still has to be learned. Hawking, according to one biographer, did so little revision at Oxford he decided to focus on theoretical questions in his final exams rather than get caught out on those that required recalling facts. This is the puzzle it’s hard for us non-geniuses to understand.

One explanation is that they start school with great enthusiasm but quickly tire of it, forced to crawl along the curriculum when they should be running. “Just because you are highly able does not necessarily mean that you will achieve to a corresponding level,” says Jae Jung, an associate professor at the University of New South Wales who has a research interest in gifted children.

“One of the reasons we have so much of this underachievement happening is that teachers are not trained in giftedness, which means that these gifted kids are not being looked after. They’re being given content that’s, say, three years below their level of capability so they’re bored, they’re not going to do the work, hence they’re not achieving to their full potential.”

According to Parker, there is “virtually no” training for teachers in giftedness at an undergraduate level. She also says a number of studies have shown that teachers are not very capable at detecting the gifted children in their classrooms.

‘There’s always this focus on the kids who are struggling and, of course, they need support. But ... the kids at the other end need support as well.’

Isabella tells us at her old school she would finish an hour’s work in six minutes then stare at the ceiling for the rest of the class. Another mother worries that her gifted daughter – whose interests range from teleportation to the origins of the Christian calendar – is losing her initial love of learning. “They disengage and tune out and don’t find it interesting,” she says. “We want her to strive for more and not think, oh, this isn’t for me, I’m not that smart because I’m not doing well at school, and just give up.”

“It’s still about engagement,” says Harman, who is principal at Melbourne’s Balwyn High School. “It’s still about inspiring them.” Often, she says, underperformance can be tied to self-esteem or a student’s relationships with classmates. “There can be kids who underperform because they don’t want to reveal how talented they are.”

Then there are the “twice exceptional” children, who might show indications of giftedness but who fail to shine at school because of an accompanying learning impediment such as autism spectrum disorder or ADHD. A study of US members of Mensa, the international club whose price of admission is a high IQ, found that high intelligence often co-exists with super-sensitivities.

“What’s extremely difficult about having those two things combined,” says a mother with a gifted daughter, “is that children like this, their natural intelligence kind of floats them through at a decent level. Not at a high level, but at a level that is still above a lot of other kids, which is what we’re experiencing. And the school will say, ‘Well, they’re doing fine. They’re getting Cs or maybe occasional Bs’. But it’s relative to how smart you know your child is and how you think they should be doing.”

Does it matter? Haven’t these children already effectively won the intellectual lottery? Obviously, their emotional welfare must be considered, along with that of every other child. But their underperformance is also Australia’s loss, at least according to the Victorian parliamentary inquiry, which estimated between 10 and 50 per cent of gifted children were failing to reach their potential. “Gifted students are our prospective leaders and innovators. In nurturing their talents, we are not only meeting their rights to access an appropriate education, but also ensuring that the future of our society is in good hands.”

An earlier government inquiry, from 1988, concluded that gifted children were among the lowest priorities of all educationally disadvantaged groups. Jae Jung puts it this way. “There’s always this focus on the kids who are struggling and, of course, they need support. But just as they need support, the kids at the other end need support as well. The fact that they’re not being appropriately supported is demonstrated by the long declining trend in the performance of Australian students at the top end in international assessments”.

Australia has been slipping down the international rankings of the thrice-yearly Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) tests since its inception in 2000. In 2019, this masthead reported “alarm bells” as the proportion of Australian students among the low performers increased while the proportion of the high performers decreased.

Isabella’s first school did not believe that “giftedness was a thing”, says her mum. ”Therefore, every child was to finish the year at the same level. At first, Isabella desperately wanted to go to school. But she learned very quickly that it was easier to hide.” She was so bored and frustrated in class she ground down her front teeth (“they’re actually damaged,” she says).

After years of struggles, including a period of home-schooling, her parents finally enrolled her in a private school’s remote learning program where the class levels are appropriate for ability, not necessarily age. Isabella is clearly much happier these days.

“It’s a pretty good school,” she says. “There’s about six kids in my class and most of them are like me. It’s very focused on individuals. It’s pretty advanced stuff, too. It’s not like normal schooling. So we get a lot done.”

And her advice to other gifted children? “They’re obviously going to be different and you have to acknowledge that. Also, it’s not, like, a really good thing. So you shouldn’t just think, Oh, I’m so smart, like, everything’s going to be easy. But it’s also not really a bad thing. I guess you get used to living with it.”

Republished with permission from the Sydney Morning Herald.